Optimistic rollups represent a foundational Layer-2 scaling solution that executes transactions off-chain while inheriting Ethereum’s security guarantees through an innovative fraud proof mechanism. By processing batches of transactions outside the main chain and posting compressed data to Layer-1, optimistic rollups achieve 10-100x throughput improvements while maintaining cryptographic verifiability through economic game theory rather than computational proofs.

The architecture operates on a security assumption fundamentally different from zero-knowledge systems: transactions are presumed valid unless challenged during a dispute window, creating an optimistic trust model secured by rational economic incentives rather than cryptographic validity proofs.

The Ethereum Scalability Problem

Throughput Constraints and Economic Barriers

Ethereum’s base layer processes approximately 15-30 transactions per second, constrained by block gas limits and 12-second block times. This architectural ceiling creates two cascading problems: network congestion during demand spikes and gas prices that frequently exceed $50 per transaction during peak usage.

The economic cost structure becomes prohibitive for high-frequency applications. A simple token swap can consume 150,000 gas units; at 100 gwei base fee, this translates to $18-45 per transaction depending on ETH price volatility. For decentralized applications requiring thousands of microtransactions daily, L1 execution becomes economically infeasible.

The Scalability Trilemma Framework

Blockchain systems face an architectural constraint known as the scalability trilemma: maximizing decentralization, security, and scalability simultaneously remains computationally impossible without fundamental tradeoffs. Ethereum prioritizes decentralization (thousands of globally distributed validators) and security (cryptographic finality), accepting reduced throughput as the necessary compromise.

Layer-2 solutions emerged as the primary horizontal scaling strategy—moving execution off-chain while anchoring security to L1’s validator set. This architectural separation allows rollups to process transactions at drastically lower cost while inheriting Ethereum’s security budget (currently over $40 billion in staked ETH).

What Is a Rollup?

Conceptual Architecture

A rollup is a blockchain execution environment that processes transactions off-chain, bundles them into compressed batches, and posts commitment data to Ethereum L1. The fundamental innovation lies in state computation separation: execution happens in the rollup environment, while data availability and dispute resolution occur on the base layer.

Three components define the rollup model:

- Off-chain execution: Transactions are processed by rollup sequencers using standard EVM bytecode (or modified virtual machines)

- Data compression: Transaction batches are compressed and posted to L1 as calldata or blob storage

- State commitments: Merkle roots representing the rollup’s state tree are anchored on-chain periodically

L1 Security Inheritance Mechanism

Rollups inherit security by making L1 the ultimate arbiter of validity. The base layer serves three critical functions:

- Data availability layer: All transaction data must be retrievable from L1 to reconstruct state independently

- Settlement layer: State transitions are finalized only after L1 confirmation and challenge period expiration

- Dispute resolution layer: L1 smart contracts adjudicate fraud proofs through deterministic execution verification

This architecture means a rollup cannot be compromised unless Ethereum itself suffers a consensus failure—the rollup’s security budget equals Ethereum’s validator set, not the rollup’s own infrastructure.

Batch Compression Economics

Transaction batching creates the economic efficiency gain. Instead of posting each transaction individually to L1 (consuming 21,000+ gas per tx), rollups compress hundreds or thousands of transactions into a single batch. A batch containing 1,000 transactions might consume 500,000 gas total—reducing per-transaction L1 cost to 500 gas, a 40x improvement.

Post-EIP-4844, rollups can publish data to blob storage at substantially lower cost than calldata. Blob gas operates in a separate fee market with targets of 3-6 blobs per block (increased to 6-9 after Pectra upgrade), creating periods where data availability costs approach near-zero.

Optimistic Rollups Explained

The Optimistic Assumption Model

Optimistic rollups operate on a trust-but-verify paradigm: state transitions are assumed correct by default unless a validator proves otherwise. This assumption inverts the zk-rollup model, which requires cryptographic proofs for every batch before acceptance.

The security guarantee rests on a 1-of-N honesty assumption—only a single honest verifier is required to detect and prove fraud. This asymmetry creates a powerful security property: attacking the system requires compromising or censoring all potential validators simultaneously, while defending requires just one honest actor with L1 access.

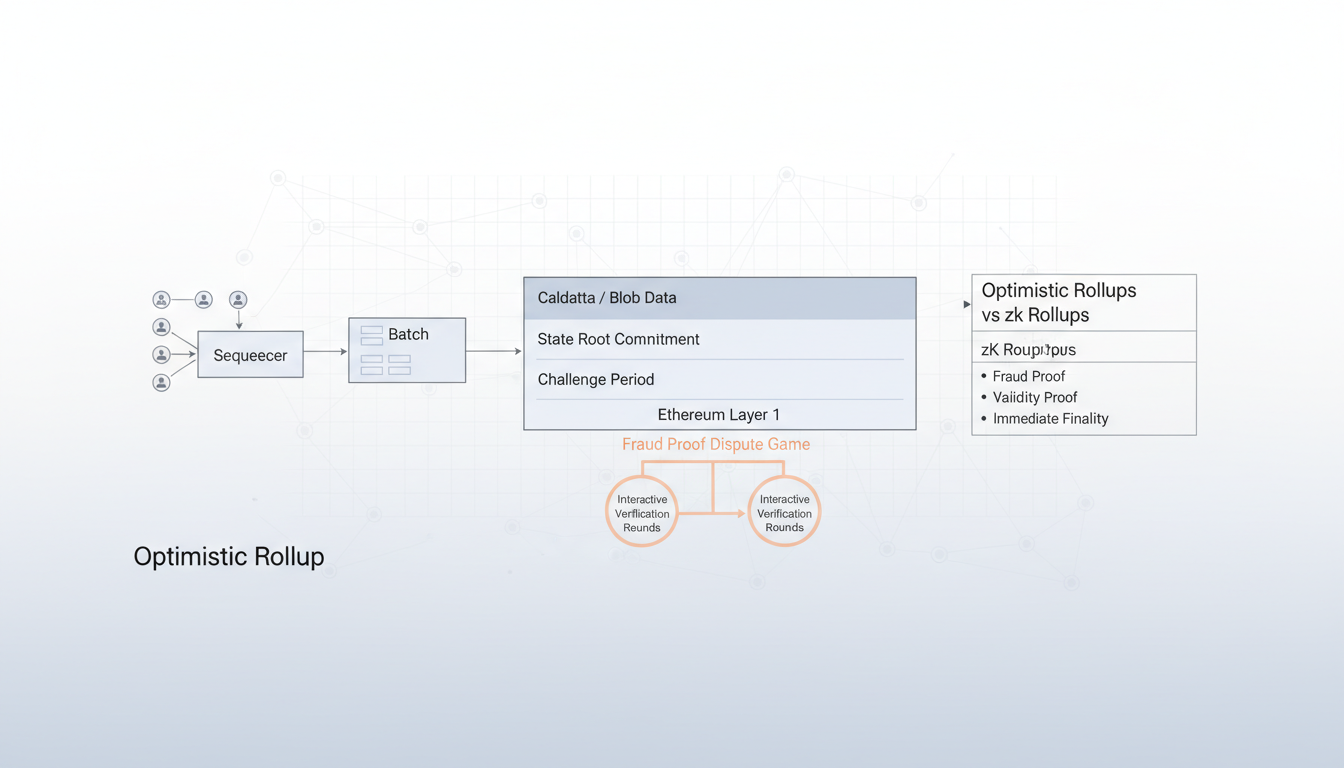

Sequencer Role and Transaction Lifecycle

The sequencer operates as the primary transaction ordering engine. Users submit transactions to the sequencer’s mempool, which orders them, executes state transitions, and produces blocks with sub-second latency. Current implementations use centralized sequencers (Optimism, Arbitrum, Base all run single-operator sequencers).

Sequencer centralization creates a trust assumption for liveness and censorship resistance, but not for validity—a malicious sequencer cannot steal funds or create invalid state, only delay or censor transactions. Decentralized sequencer networks represent active research (Espresso, Astria, shared sequencing), though none have achieved production deployment at scale as of February 2026.

Transaction Batching and State Commitment

The sequencer aggregates transactions into batches at regular intervals (typically every few minutes to hours, depending on network activity). Each batch contains:

- Compressed transaction data: Function calls, signatures, and state diffs encoded efficiently

- Previous state root: Merkle root of the rollup state tree before batch execution

- New state root: Merkle root after applying all transactions in the batch

- Execution trace commitment: Hash of intermediate states during execution (used for fraud proof bisection)

This batch is posted to an L1 contract, consuming gas proportional to data size. The contract stores the state root claim without verifying correctness—verification happens optimistically through the fraud proof mechanism.

Posting Calldata vs Blobs to Layer-1

Pre-EIP-4844, rollups posted transaction data as calldata, which costs 16 gas per non-zero byte and 4 gas per zero byte. A 100KB batch consumed approximately 1.6M gas at full density. EIP-4844 introduced blob storage—a temporary data availability layer where each blob holds 128KB and is deleted after approximately 18 days.

Blob gas pricing operates independently with exponential adjustment based on target utilization (3 blobs per block pre-Pectra, 6 post-Pectra). During low demand periods, blob fees approach zero gwei, reducing rollup data costs by 95-99%. Rollups implement hybrid strategies: post to blobs when available and cheap, fallback to calldata during blob congestion.

Merkle Roots and State Verification

Each state commitment represents a Merkle tree root of all account states in the rollup. Validators can reconstruct this tree by:

- Downloading transaction data from L1 (either calldata or blobs)

- Re-executing transactions against the previous state root

- Computing the resulting Merkle root

- Comparing their computed root against the sequencer’s posted root

Mismatch indicates invalid state transition, triggering the fraud proof process. The Merkle structure enables efficient fraud proofs—only the disputed state branch must be revealed, not the entire state tree.

Enter, Use, Exit Lifecycle

Users interact with optimistic rollups through three phases:

Deposit (Enter): Users lock funds in an L1 bridge contract, which emits an event the sequencer monitors. The sequencer credits equivalent balance in the rollup state, typically within minutes.

Transact (Use): Users submit transactions directly to the sequencer, receiving near-instant soft confirmations (pre-consensus). These transactions achieve L1 finality once included in a batch posted to mainnet plus the challenge period.

Withdraw (Exit): Users initiate withdrawal by burning rollup balance and submitting a withdrawal proof. After the challenge period expires (7 days for Optimism/Arbitrum), users can claim funds from the L1 bridge contract.

The 7-day withdrawal delay represents the critical UX tradeoff of optimistic rollups—required to ensure fraud proof submission time, but creating significant capital efficiency costs.

Fraud Proof System: Security Through Economic Game Theory

What Is a Fraud Proof?

A fraud proof is a cryptographic demonstration that a state transition posted to L1 contains computational errors. Unlike validity proofs (used in zk-rollups) which prove correctness, fraud proofs prove incorrectness—they are only generated when fraud occurs.

The proof consists of:

- State root claim: The disputed state commitment posted by the sequencer

- Execution trace: Step-by-step record of computation during batch processing

- Merkle witnesses: Proofs showing specific state elements existed in the pre-state tree

- Single-step verification: A single computational step (e.g., one EVM opcode) that produces different results than claimed

Interactive Dispute Protocol and Bisection

Current production optimistic rollups use interactive fraud proofs rather than non-interactive proofs. When a validator challenges a state root, the protocol initiates a multi-round bisection game:

Round 1: The challenger and defender submit execution traces divided into N segments (e.g., 512 segments for Optimism). They identify the first segment where their traces diverge.

Round 2-K: The disputed segment is recursively bisected until reaching a single computational step—typically a single EVM instruction.

Final Resolution: L1 executes the disputed instruction on-chain using provided witnesses. The party whose result matches L1’s deterministic execution wins; the losing party forfeits their bond.

Arbitrum uses multi-round fraud proofs with logarithmic complexity—a batch of 1 billion instructions requires only log₂(1B) ≈ 30 rounds to resolve. Optimism historically used single-round proofs but migrated to multi-round “fault proofs” in 2024-2025.

Challenge Period Economic Rationale

The challenge period (typically 7 days) must satisfy two constraints:

- Sufficient duration for verification: Validators need time to download batch data, re-execute transactions, detect fraud, and submit challenges even under adversarial network conditions

- Censorship resistance buffer: If a malicious sequencer attempts L1 censorship, honest validators must have time to bypass censorship (via alternative RPCs, MEV bundles, or direct validator submission)

The 7-day window far exceeds the computational time required (fraud detection takes minutes with adequate infrastructure). The extended period primarily guards against L1 censorship attacks and provides redundancy for validator liveness failures.

Verifier Incentives and Game Theory

The fraud proof mechanism relies on at least one rational validator continuously monitoring the rollup. Game-theoretic analysis reveals a critical challenge: the verifier’s dilemma.

Verifier’s Dilemma: If fraud never occurs, verifiers expend resources (computational cost, infrastructure) without receiving rewards. This creates a free-rider problem—each validator has incentive to assume others are watching, reducing their own monitoring to save costs.

Research demonstrates this creates a mixed equilibrium where validators probabilistically monitor rather than continuously verify. To address this, proposed solutions include:

- Proof of Diligence: Validators submit cryptographic evidence of execution (VRF-based proofs tied to execution traces) to earn rewards even in normal operation

- Watchtower networks: Dedicated entities paid to continuously monitor rollups, with slashing for non-performance

- Attention challenges: Periodic test transactions where validators must prove they detected intentional errors

As of February 2026, no production optimistic rollup has implemented fully decentralized watchtower incentives, creating a security assumption that altruistic or commercially motivated entities (bridge operators, DEX frontends) perform verification.

The Dispute Game and Economic Incentives

Validator Deposits and Slashing Conditions

Participants in fraud proof disputes must post bonds to prevent spam attacks. Typical bond structures:

- Challenger bond: 0.01-0.1 ETH posted when initiating a dispute

- Defender bond: Posted by the state proposer, typically 1-10 ETH per batch

If the challenger proves fraud, they receive the defender’s bond (or a portion, depending on protocol parameters). If the challenge fails, the challenger loses their bond. This asymmetry creates an economic cost for frivolous challenges while rewarding legitimate fraud detection.

Challenge Period Economics

The 7-day withdrawal delay creates a fundamental UX limitation. For users, this manifests as:

- Capital inefficiency: Funds are locked during withdrawal, creating opportunity costs

- Liquidity fragmentation: Third-party bridges offer instant withdrawals by providing liquidity, but introduce additional trust assumptions and extract fees (typically 0.1-0.3%)

For protocols, the delay impacts composability—cross-rollup atomic transactions become impossible without trusted intermediaries.

Auction Attacks and Validator Competition

Recent game-theoretic analysis reveals a structural vulnerability: malicious proposers can deploy auction mechanisms to minimize their fraud costs. The attack vector:

- A malicious proposer submits invalid state and posts the required bond

- When challenged, the proposer deploys an auction contract offering a portion of the bond as reward

- Validators compete in a second-price auction to win the “first dispute completion” prize

- The winning validator pays nearly their full expected reward in auction fees, reducing net profit to near-zero

This attack demonstrates that increased validator participation counterintuitively reduces effective security—more challengers means higher auction competition and lower individual challenger profit. Proposed mitigations include escrowed rewards (delay distribution until all challenges resolve) and commit-reveal challenge schemes.

Verifier’s Dilemma: Deep Dive

Formal game-theoretic modeling demonstrates the core incentive misalignment:

Scenario 1: If all validators assume others will catch fraud, no validator has individual incentive to verify (verification costs exceed zero reward in honest equilibrium).

Scenario 2: If one validator verifies while others do not, that validator bears full computational cost but receives the same security benefit as free-riders.

This creates a mixed Nash equilibrium where validators randomize their verification probability, resulting in non-deterministic security. The probability that fraud goes undetected increases exponentially with the number of potential verifiers who all employ mixed strategies rather than deterministic monitoring.

Mathematical analysis shows the optimal fraud detection rate requires either:

- Subsidized rewards during normal operation (Proof of Diligence approach)

- Reputation mechanisms where validator identity and historical performance create long-term incentive alignment

- Forced participation through attention challenges with slashing for non-response

Multi-Challenge Attack Scenarios

An adversary controlling multiple validator identities can exploit the dispute mechanism through:

Griefing attacks: Submit numerous invalid challenges to force defenders to lock capital in bonds and expend resources responding to disputes.

Capital exhaustion: If bond sizes are significant, force honest validators to distribute capital across defending multiple simultaneous challenges, reducing their ability to challenge other invalid states.

Censorship amplification: Combined with L1 censorship, delay resolution of valid challenges beyond the challenge window by flooding the dispute queue.

Mitigations include progressive bond requirements (higher bonds for validators with challenge histories) and reputation-weighted dispute queues.

Withdrawal Delays and Challenge Window Design

Why Withdrawals Take 7 Days

The 7-day delay serves as the fraud proof submission deadline. The period must accommodate:

- Data availability verification: Validators must download and verify batch data is available from L1

- Re-execution time: Compute resources required to re-execute all transactions in the batch

- Fraud proof generation: If fraud is detected, construct and submit the fraud proof

- Interactive dispute resolution: Complete all rounds of the bisection protocol

- Censorship resistance buffer: Account for potential L1 censorship attempts that require alternative submission paths

While steps 1-4 typically complete within hours given adequate infrastructure, the censorship buffer dominates the security analysis. If an adversary controls significant L1 block proposal power, they might censor fraud proofs for extended periods.

Security Rationale and Attack Resistance

The challenge window creates security through asymmetric costs:

Attack cost: To successfully withdraw fraudulent funds, an attacker must:

- Control the rollup sequencer (to create invalid state)

- Censor all fraud proofs on L1 for the entire 7-day window

- Avoid detection by any of the potentially thousands of independent validators

Defense cost: A single honest validator with L1 access can:

- Detect fraud (computational cost: $1-10 in cloud resources)

- Submit fraud proof (transaction cost: ~$50-500 in gas fees)

- Trigger dispute resolution (bonded, but returned if challenge succeeds)

This asymmetry—requiring an attacker to sustain majority L1 censorship while a defender needs only a single successful transaction—creates the security guarantee.

Fast Bridges vs Canonical Bridge Risks

Third-party bridges offer instant withdrawals by providing liquidity upfront and claiming from canonical bridges after the 7-day delay. These introduce trust assumptions:

Liquidity provider risk: If the rollup batch is successfully challenged and invalidated, the liquidity provider loses funds provided to users.

Solvency assumptions: Fast bridges operate as fractional reserve systems—if withdrawal demand exceeds available liquidity, withdrawals delay anyway.

Smart contract risk: Additional smart contract attack surface beyond the core rollup protocol.

Users effectively trade security (canonical bridge backed by fraud proofs) for speed (fast bridge backed by liquidity provider solvency), paying a premium (typically 0.1-0.3% fees) for the service.

Data Availability in Optimistic Rollups

Why Data Availability Matters More Than Execution

Data availability (DA) represents the most critical security component of rollups. The security model requires that all transaction data must be publicly retrievable so any party can reconstruct the rollup state and verify correctness.

If transaction data is unavailable:

- Validators cannot re-execute batches to detect fraud

- Users cannot generate withdrawal proofs from rollup state

- The rollup can be censored or frozen by withholding data

Even with perfect fraud proof mechanisms, unavailable data makes the rollup insecure—validators cannot generate fraud proofs for batches they cannot access.

Calldata vs Blob Storage

Calldata (pre-EIP-4844 primary method):

- Permanently stored in Ethereum’s execution history

- Costs 4 gas per zero byte, 16 gas per non-zero byte

- Accessible indefinitely through archive nodes

- Creates permanent state growth (scalability limitation)

Blob storage (post-EIP-4844):

- Temporary availability (~18 days retention)

- Separate blob gas market with exponential pricing

- Pruned after retention window, reducing L1 storage burden

- Requires rollups to maintain archival copies for historical data

EIP-4844 introduced blob gas as a distinct resource from execution gas, with blob target/max of 3/6 blobs per block (increased to 6/9 after May 2025 Pectra upgrade). Blob base fee adjusts based on usage:

- If blocks contain >6 blobs: blob base fee increases 12.5% per block

- If blocks contain <6 blobs: blob base fee decreases 12.5% per block

Data Availability Layers and Modular Architecture

The modular blockchain thesis separates data availability from execution and settlement. Alternative DA layers include:

Celestia: Dedicated DA blockchain using data availability sampling (DAS) for light client verification. Promises 100x cost reduction vs Ethereum blobs for equivalent security.

EigenDA: Leverages Ethereum’s validator set through restaking, providing DA with native ETH economic security but separate bandwidth.

Avail: Standalone DA layer with polynomial commitments for efficient data availability proofs.

Using non-Ethereum DA creates a security assumption tradeoff—the rollup’s security no longer depends solely on Ethereum’s consensus but also on the alternative DA layer’s integrity. This architecture is sometimes termed “validium” (when using zero-knowledge proofs) or “optimium” (when using optimistic verification with external DA).

Proto-Danksharding (EIP-4844) and Blob Economics

EIP-4844 implemented proto-danksharding, a transitional architecture before full danksharding with data availability sampling. Key parameters:

- Blob size: 128 KB each (4,096 field elements × 32 bytes)

- Target/max: 6/9 blobs per block post-Pectra (doubled from 3/6)

- Retention: ~4,096 epochs (≈18 days) before pruning

- Commitment scheme: KZG commitments for efficient verification without downloading full blobs

Blob pricing creates significant economic advantages:

During low blob demand, blob base fee approaches zero, reducing rollup batch cost from $50,000-500,000 (calldata) to under $100 (blobs). Post-Pectra, increased blob target reduced competition further, creating sustained periods of near-zero blob costs.

Rollups implement dynamic posting strategies:

- Monitor blob base fee and calldata gas price

- Post to blobs when blob_fee < calldata_fee × compression_ratio

- Fallback to calldata during blob congestion

Future: Full Danksharding and Data Availability Sampling

Full danksharding will introduce data availability sampling, enabling light clients to verify data availability without downloading entire blobs. The mechanism:

- Blobs are extended using erasure coding (any 50% of data can reconstruct the full blob)

- Light clients randomly sample small portions of the extended data

- If all samples are available, data availability is guaranteed with high probability

- Blob targets increase from 6 to 64+ blobs per block, proportionally reducing DA costs

This enables horizontal scaling of DA capacity while maintaining light client verifiability—the critical scalability bottleneck in current architecture.

Optimistic Rollups vs zk Rollups: Technical Comparison

Fraud Proofs vs Validity Proofs: Core Security Models

The fundamental distinction lies in verification timing and cryptographic approach:

Optimistic rollups (fraud proofs):

- Assume validity unless challenged

- Proofs generated only when fraud occurs (reactive verification)

- Proof size: ~100-500 KB for interactive disputes

- Verification cost on L1: Single EVM instruction execution (~5,000-50,000 gas)

zk rollups (validity proofs):

- Prove validity cryptographically before acceptance

- Proofs generated for every batch (proactive verification)

- Proof size: ~200-500 KB for SNARKs/STARKs

- Verification cost on L1: Pairing operations or FRI verification (~250,000-600,000 gas)

This asymmetry creates opposite security-efficiency tradeoffs.

Prover Costs and Hardware Requirements

Optimistic rollups:

- Sequencer runs standard EVM execution (commodity hardware sufficient)

- No specialized cryptographic operations required

- Prover cost per transaction: ~$0.0001-0.001 (standard computation)

- Fraud proof generation occurs only when challenging (rare event)

zk rollups:

- Prover generates cryptographic proofs for every batch

- Requires specialized hardware (GPU/FPGA/ASIC for performance)

- Prover cost per transaction: ~$0.01-0.10 depending on proof system

- Operational costs 10-100x higher than optimistic equivalents

As of February 2026, zk-rollup prover costs remain the primary economic bottleneck, though improvements in proof systems (Plonky2, Binius, Circle STARKs) are reducing costs by 10x annually.

Finality Time and Withdrawal Latency

Optimistic rollups:

- Soft finality: Instant (sequencer confirmation)

- L1 finality: 12-15 minutes (batch posted to L1 + Ethereum finality)

- Economic finality: 7 days (after challenge period)

- Withdrawal time: 7 days to canonical bridge

zk rollups:

- Soft finality: Instant (sequencer confirmation)

- L1 finality: 12-15 minutes (batch posted + proof verified)

- Economic finality: 12-15 minutes (same as L1 finality)

- Withdrawal time: 15-60 minutes (proof generation + L1 confirmation)

The 7-day withdrawal delay represents the primary UX disadvantage of optimistic rollups. For applications requiring fast finality (CEX withdrawals, cross-chain bridges), zk-rollups provide superior user experience.

EVM Compatibility and Developer Experience

Optimistic rollups:

- Near-perfect EVM equivalence (Optimism, Arbitrum execute unmodified Solidity)

- Existing tooling (Hardhat, Foundry, Remix) works without modification

- Gas metering identical to L1 (with minor adjustments)

- Smart contract migration requires minimal or zero code changes

zk rollups:

- EVM compatibility requires proving EVM execution in zero-knowledge

- zkEVM implementations (Polygon zkEVM, zkSync Era, Scroll) have varying compatibility levels

- Some zk-rollups use custom VMs (Cairo for StarkNet) requiring language rewrites

- Gas costs differ substantially due to proof generation overhead

As of February 2026, optimistic rollups maintain superior EVM equivalence, though zkEVM compatibility has improved significantly (Polygon zkEVM achieves type-2 equivalence, differing only in gas costs).

Security Assumptions and Trust Models

Optimistic rollups:

- Require 1-of-N honest validator assumption

- Depend on data availability from L1

- Vulnerable to verifier’s dilemma (incentive misalignment)

- Censorship resistance requires L1 liveness during challenge period

zk rollups:

- Zero-trust validity (cryptographic certainty of correctness)

- Depend on data availability from L1

- Require trusted setup for some proof systems (SNARKs), not others (STARKs)

- No economic game theory vulnerabilities

zk-rollups provide strictly stronger security guarantees—they eliminate fraud scenarios entirely through mathematical proof. The tradeoff is substantially higher computational cost and reduced EVM compatibility.

Comparison Table

Real Implementations: Production Optimistic Rollups

Arbitrum

Architecture: Multi-round interactive fraud proofs with WebAssembly (WASM) execution environment. Arbitrum compiles EVM bytecode to WASM, then generates fraud proofs at WASM instruction granularity.

Key Technical Details:

- Fraud proof rounds: ~30 rounds for bisection to single instruction

- Challenge period: 7 days

- Sequencer: Centralized (operated by Offchain Labs)

- Data availability: EIP-4844 blobs (fallback to calldata)

- State commitment frequency: Variable based on activity (typically 15-60 minutes)

Architectural Innovations:

- AnyTrust: Optional mode using Data Availability Committee (DAC) for cheaper DA at reduced security

- Arbitrum Orbit: Framework for deploying custom L2/L3 chains using Arbitrum technology

- Stylus: Enables smart contracts in Rust/C++ compiled to WASM, offering 10-100x gas efficiency vs Solidity

As of February 2026: ~$8-12B TVL, processing 3-5M transactions daily.

Optimism

Architecture: Initially single-round fraud proofs, migrated to multi-round “fault proofs” in 2024. Uses cannon (on-chain MIPS emulator) for fraud proof verification.

Key Technical Details:

- Fraud proof: Multi-round bisection to single MIPS instruction

- Challenge period: 7 days

- Sequencer: Centralized (operated by OP Labs)

- Data availability: EIP-4844 blobs (primary), calldata (fallback)

- State commitment: Every 30-120 minutes

Architectural Innovations:

- OP Stack: Modular framework for deploying custom L2s (used by Base, Mode, Blast)

- Superchain vision: Shared security and interoperability across OP Stack chains

- Modular DA: Support for alternative DA layers (Celestia, EigenDA) in roadmap

As of February 2026: ~$4-7B TVL, processing 1-2M transactions daily.

Base

Architecture: Deployed using OP Stack, operated by Coinbase.

Key Technical Details:

- Inherits Optimism’s fault proof mechanism

- Challenge period: 7 days

- Sequencer: Centralized (Coinbase-operated)

- Data availability: EIP-4844 blobs

Distinguishing Features:

- Coinbase integration: Direct fiat on/off ramps, native USDC support

- Centralization trade-off: Prioritizes operational simplicity over immediate decentralization

- Consumer application focus: Designed for high-throughput consumer apps (social, gaming)

As of February 2026: ~$3-6B TVL, processing 2-4M transactions daily.

Metis

Architecture: Fork of Optimism with modifications for decentralized sequencing.

Key Technical Details:

- Sequencer: Rotating sequencer pool (partially decentralized)

- Data availability: Hybrid model with off-chain storage + on-chain commitments

- Challenge period: 7 days

Distinguishing Features:

- First optimistic rollup to deploy decentralized sequencer rotation

- Reduced L1 data posting through off-chain DA (trust assumption vs Ethereum-only DA)

Boba Network

Architecture: Optimism fork with hybrid compute and liquidity improvements.

Key Technical Details:

- Fast exits: Liquidity pools enable exits in minutes (trust assumption on LP solvency)

- Hybrid compute: Integration with off-chain compute for certain operations

- Challenge period: 7 days for canonical bridge

These implementations demonstrate architectural diversity within the optimistic rollup design space—ranging from maximal EVM equivalence (Optimism, Arbitrum) to hybrid trust models (Metis, Boba) and application-specific optimizations (Base’s consumer focus).

Attack Vectors and Known Risks

Centralized Sequencer Risks

All production optimistic rollups currently operate centralized sequencers. This creates several attack surfaces:

Liveness failure: If the sequencer goes offline, users cannot submit transactions until it recovers. Mitigations include forced inclusion mechanisms—users can submit transactions directly to L1 contracts, forcing the sequencer to include them or forfeit their role.

Censorship: The sequencer can selectively exclude transactions. While users can bypass via L1 forced inclusion, this increases cost and latency. Long-term censorship resistance requires decentralized sequencer networks.

MEV extraction: Centralized sequencers capture all MEV (maximal extractable value) from transaction ordering. This creates unaccountable revenue—Arbitrum’s sequencer generates $50-100M annually in sequencing revenue not shared with users or token holders.

Single point of failure: Infrastructure compromise (AWS outage, DDoS attack) can halt the entire rollup. Geographic and infrastructure diversity in decentralized sequencers reduces this risk.

Economic Griefing Attacks

Attackers can exploit the dispute mechanism to impose costs on honest parties:

Bond exhaustion: Submit multiple invalid challenges forcing defenders to lock capital in dispute bonds. Even if challenges ultimately fail, defenders face liquidity costs and operational overhead.

Auction exploitation: As demonstrated in recent research, malicious proposers can deploy auction mechanisms to minimize their fraud costs by forcing challenger competition. Validators competing for fraud bounties drive auction prices to near their expected reward, reducing net challenger profit to zero.

Computational griefing: Submit marginally invalid states requiring extensive re-execution to detect. While fraud proofs will succeed, validators expend disproportionate resources relative to attacker costs.

Mitigations include progressive bonding (higher bonds for repeated challengers), reputation systems, and escrowed reward mechanisms.

Malicious Proposer Strategies

An attacker controlling the state proposer role can execute several strategies:

Invalid state + censorship: Post invalid state while simultaneously censoring fraud proofs on L1. Success requires sustained majority L1 block production (>50% for 7 days), making this attack extremely expensive.

Invalid state + bribery: Pay L1 validators to censor fraud proofs. Game-theoretic analysis shows this requires bribes exceeding the stolen amount plus the proposer’s bond, making it economically irrational.

Data withholding: Post state commitments without publishing full transaction data. This prevents validators from generating fraud proofs. Mitigations include requiring data availability proofs (blobs include KZG commitments) and timeout mechanisms if data is unavailable.

Data Withholding Attacks

If transaction data is not available, validators cannot verify or challenge state transitions. Attack scenarios:

Blob non-publication: Sequencer posts state commitments claiming blob references but doesn’t actually publish blobs to the P2P network. Mitigations: consensus clients must attest to blob availability before inclusion.

Selective withholding: Publish data to some nodes but not others, attempting to prevent specific validators from challenging. Mitigations: redundant data availability verification across multiple consensus clients.

Post-pruning unavailability: After the ~18-day blob retention window, historical data becomes unavailable from L1. Rollups must maintain archival copies; absence creates trust assumption in rollup operators for historical verification.

Multi-Challenge Collusion

Multiple attackers could collude to exhaust defender resources:

Simultaneous challenges: Submit coordinated challenges to different batches, forcing defenders to split capital across multiple disputes.

Cyclic challenges: After losing a dispute, immediately re-challenge with a different identity, creating endless dispute loops. Mitigations include progressive bond increases and challenge rate limits.

Validator set capture: If all independent validators are compromised or colluding, fraud can proceed undetected. The 1-of-N security model breaks down to 0-of-N. This represents the ultimate failure mode, requiring at least one honest validator with L1 access to maintain security.

Future of Optimistic Rollups

Decentralized Sequencer Networks

Centralized sequencers represent the primary trust assumption in current deployments. Multiple approaches to decentralization are under development:

Shared sequencing (Espresso, Astria): Multiple rollups share a decentralized sequencer network, providing atomic cross-rollup composability and eliminating individual rollup liveness risk.

Based sequencing: Rollups delegate sequencing directly to L1 validators, inheriting Ethereum’s decentralization and censorship resistance properties. L1 validators include rollup transactions in their blocks and receive sequencing fees.

Leader rotation: Rotate sequencer role among bonded operators (similar to validator rotation in PoS). Implemented partially by Metis; under development for Arbitrum and Optimism.

As of February 2026, no major optimistic rollup has fully decentralized sequencing in production, though testnet deployments (Espresso integration with OP Stack) are progressing.

Fault Proofs v2 and Faster Finality

Research into accelerated dispute resolution aims to reduce the 7-day challenge period:

Dynamic fraud proofs: Achieve sub-second finality in normal scenarios while dynamically extending challenge periods only when disputes occur.

Optimistic TEE-Rollups: Use trusted execution environments (TEEs) for provisional finality with optimistic verification and ZK spot-checks.

Multi-prover systems: Require multiple independent provers to agree on state, reducing the probability of undetected fraud and enabling shorter challenge windows.

These approaches trade increased operational complexity for improved UX through faster withdrawals.

Hybrid zk + Optimistic Architectures

Emerging designs combine optimistic and zero-knowledge proof systems:

zk fraud proofs: Instead of interactive bisection, use ZK proofs to demonstrate fraud in a single round. This reduces dispute resolution from days to minutes.

Optimistic proving: Generate zk proofs optimistically (lazily) only for withdrawals or when finality is required, avoiding continuous proving costs.

Validity proof fallback: Operate optimistically by default; automatically generate validity proofs if challenges occur, eliminating the challenge period for those batches.

These hybrid architectures aim to capture optimistic rollups’ low operational costs with zk-rollups’ fast finality.

Layer-3 Rollups and Modular Stacks

L3 architectures use L2 optimistic rollups as settlement layers for additional L3 chains:

Security model: L3 inherits L2 security (which inherits L1 security), creating a nested trust model. L3 fraud must be detected before L2 batches finalize (~7 days), adding complexity.

Use cases: Application-specific chains with custom gas tokens, privacy features, or alternative VMs. Arbitrum Orbit and OP Stack both support L3 deployment.

Economic advantages: L3s batch to L2 instead of L1, reducing DA costs by another order of magnitude during low L2 activity periods.

The modular thesis suggests specialized layers for execution (L2/L3), settlement (L2), data availability (Celestia, EigenDA), and consensus (Ethereum L1), with optimistic rollups serving as settlement and execution layers in this stack.

Modular Data Availability

Alternative DA layers promise 100x cost reductions vs Ethereum blobs:

Celestia: Dedicated DA blockchain with data availability sampling, enabling light clients to verify DA without downloading full blocks.

EigenDA: Leverages Ethereum’s validator set via restaking; validators opt-in to provide DA bandwidth for additional yield.

Avail: Standalone DA layer with validity proofs for data availability.

Using non-Ethereum DA creates a security tradeoff—rollup security depends on both Ethereum (for settlement/fraud proofs) and the DA layer (for data availability). This is sometimes termed “optimium” (optimistic rollup with external DA) or “plasma-like” architecture.

The economic advantage: Ethereum blobs cost $0.001-1 per KB during high demand; alternative DA layers target $0.00001-0.0001 per KB.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is an optimistic rollup?

An optimistic rollup is a Layer-2 scaling solution that processes transactions off-chain while inheriting Ethereum’s security through fraud proofs. The system assumes posted state transitions are valid unless challenged during a 7-day window, enabling high throughput without requiring cryptographic validity proofs for every batch.

How do optimistic rollups work?

Optimistic rollups work by batching hundreds of transactions off-chain, executing them in a separate environment, and posting compressed transaction data plus state commitments to Ethereum L1. Validators can download this data, re-execute transactions, and submit fraud proofs if they detect invalid state transitions. The fraud proof mechanism uses interactive bisection to pinpoint a single incorrect computational step, which L1 then executes to determine the dispute outcome.

What is the challenge period in optimistic rollups?

The challenge period is a 7-day window after a state commitment is posted to L1 during which validators can submit fraud proofs if they detect invalid state transitions. This period ensures sufficient time for validators to download batch data, re-execute transactions, detect fraud, and submit challenges even under adversarial network conditions including potential L1 censorship attempts.

What is a fraud proof?

A fraud proof is cryptographic evidence demonstrating that a posted state transition contains computational errors. The proof consists of execution traces, Merkle witnesses, and a single disputed computational step that L1 can verify deterministically. Modern implementations use interactive bisection protocols requiring logarithmic rounds to isolate the invalid instruction.

How are zk rollups different from optimistic rollups?

zk rollups use validity proofs that cryptographically prove every batch is correct before L1 acceptance, enabling withdrawal times of 15-60 minutes. Optimistic rollups assume validity unless challenged, requiring 7-day withdrawal delays but offering lower operational costs and superior EVM compatibility. zk rollups provide stronger security guarantees through mathematics rather than economic incentives, but face higher prover costs and hardware requirements.

Are optimistic rollups secure?

Optimistic rollups inherit Ethereum’s security under a 1-of-N honest validator assumption—only a single honest party with L1 access is required to detect and prove fraud. The security model relies on economic incentives (fraud bounties, slashing) and the asymmetric cost of attack (requiring sustained L1 censorship) versus defense (single fraud proof transaction). However, they face incentive challenges like the verifier’s dilemma, where validators may lack economic motivation to monitor continuously.

Why are withdrawals delayed in optimistic rollups?

Withdrawals require a 7-day delay to allow validators time to detect fraud and submit challenges. This period accounts for data availability verification, re-execution computation, fraud proof generation, interactive dispute resolution, and a censorship resistance buffer against potential L1 censorship of fraud proofs. The delay represents a fundamental tradeoff for optimistic security—shorter windows would reduce security margins against censorship attacks.

What are the main optimistic rollups?

The primary optimistic rollups as of February 2026 are Arbitrum (~$8-12B TVL), Optimism (~$4-7B TVL), Base (~$3-6B TVL), Metis, and Boba Network. Arbitrum uses multi-round WASM-based fraud proofs, Optimism implements multi-round MIPS-based fault proofs, Base uses OP Stack infrastructure operated by Coinbase, and Metis features partially decentralized sequencing with hybrid data availability.