Tezos staking presents a complex case for Islamic finance evaluation, with scholarly opinions diverging based on how the reward mechanism is classified under traditional Islamic contracts. The permissibility depends primarily on whether XTZ baking rewards constitute service compensation (ju’alah), partnership profits (musyarakah), or prohibited interest (riba).

Executive Summary

The question of whether Tezos staking is halal does not have a universal consensus among Islamic scholars. Recent analyses from Darul Iftaa Chicago (2025) and Malaysian Shariah authorities classify staking as potentially permissible under the ju’alah contract framework—a reward for completing a specified task—provided specific conditions are met.

What makes Tezos distinct from other proof-of-stake networks is its Liquid Proof-of-Stake (LPoS) mechanism, where delegators retain full ownership and custody of their tokens without lockup periods. The critical factor determining permissibility is not the staking mechanism itself, but rather the contractual structure, guarantee of returns, and whether the underlying blockchain serves halal purposes.

Scholars differ because cryptocurrency staking operates in a regulatory and technological space that did not exist when classical Islamic jurisprudence was formulated, requiring analogical reasoning (qiyas) to map modern practices onto traditional contract categories.

What Is Staking in Crypto?

Proof of Stake vs Proof of Work

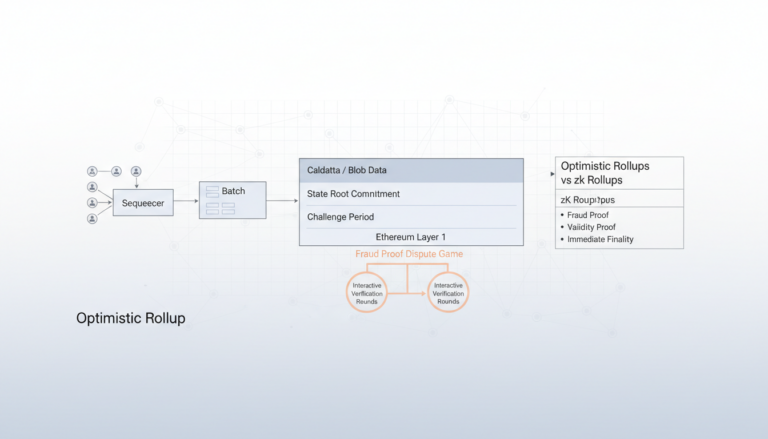

Proof-of-Stake (PoS) represents a consensus mechanism where network validators are selected to create new blocks based on the quantity of cryptocurrency they hold and are willing to “stake” as collateral. This contrasts fundamentally with Proof-of-Work (PoW) systems like Bitcoin, where validators (miners) must solve computational puzzles using significant electricity and hardware resources.

In PoS networks, validators secure the blockchain by locking cryptocurrency tokens, which creates economic incentive alignment—validators risk losing their stake if they validate fraudulent transactions. The selection process for validators typically combines randomization with stake size, ensuring that those with larger stakes have proportionally higher chances of being selected while preventing complete centralization.

What Validators Actually Do

Validators in PoS systems perform critical network security functions: verifying transaction authenticity, creating new blocks, maintaining consensus across the distributed network, and participating in governance decisions. These are active computational services, not passive holdings.

The Nature of Staking Yields

Staking rewards represent newly minted tokens distributed through network inflation, combined with transaction fees collected from network users. These rewards are not “free money” but compensation distributed to validators for providing network security infrastructure and computational resources.

In most PoS networks, rewards are variable and depend on multiple factors: total network stake, individual validator performance, network participation rates, and protocol parameters. This variability distinguishes staking from fixed-income instruments in traditional finance.

How Tezos Staking (Baking) Actually Works

Delegated Liquid Proof of Stake (LPoS)

Tezos implements a unique variant called Liquid Proof-of-Stake that differs significantly from standard delegated PoS systems used by networks like BNB Chain. In Tezos LPoS, there is no fixed number of validators (called “bakers”), and delegation does not require token lockup or transfer of ownership.

The Baker Role

Bakers are nodes that actively validate transactions and create new blocks on the Tezos blockchain. Unlike other PoS systems with high infrastructure requirements, Tezos allows bakers to operate with relatively modest hardware specifications. Bakers must bond a minimum amount of XTZ tokens (currently 6,000 XTZ per rolling cycle) to participate in consensus.

Delegation Mechanism

Token holders who do not wish to run baker nodes can delegate their XTZ to existing bakers. Crucially, this delegation does not transfer ownership or custody of tokens—delegators maintain complete control over their XTZ in their own wallets. Delegators can change their chosen baker at any time without withdrawal delays or penalties.

Reward Generation Mechanics

Tezos generates new tokens through protocol-defined inflation, with bakers receiving approximately 20 XTZ per perfectly validated block, plus transaction fees. The annual inflation rate started at approximately 5.5% and decreases gradually each year as the total supply increases. Bakers distribute a portion of these rewards to their delegators, typically retaining a service fee ranging from 5-15%.

Slashing Risk

Tezos implements minimal slashing compared to networks like Ethereum. Validators face penalties primarily for double-baking (attempting to create two blocks at the same height) or double-endorsing, but the risk is significantly lower than in other PoS systems.

Custody and Control

A defining feature for Shariah analysis: delegated XTZ never leaves the delegator’s wallet address. Cryptographic proof demonstrates that ownership transfer does not occur, distinguishing delegation from lending (qarḍ) which requires ownership transfer under Islamic law.

Islamic Finance Framework for Evaluation

Core Shariah Principles

Riba (Usury/Interest): Any excess compensation in a loan transaction where the lender receives guaranteed return beyond the principal. Riba is strictly prohibited in multiple Quranic verses and represents exploitation through guaranteed fixed returns without risk-sharing.

Gharar (Excessive Uncertainty): Transactions with excessive ambiguity regarding essential terms, outcomes, or deliverables. Moderate uncertainty is tolerated, but contracts where fundamental elements remain unknown are prohibited.

Maisir (Gambling/Speculation): Wealth transfer dependent primarily on chance rather than productive economic activity. Distinguished from legitimate risk-taking in business ventures by the absence of underlying asset productivity.

Qimar (Games of Chance): Activities resembling gambling where outcomes are determined predominantly by luck rather than skill or economic contribution.

Milk (Ownership): Valid Islamic contracts require clear establishment of ownership rights and responsibilities. Transfer or retention of ownership affects contract classification fundamentally.

Risk Sharing (Musyarakah Principle): Islamic finance emphasizes profit-and-loss sharing where all parties bear proportional risk. Guaranteed returns that eliminate risk for capital providers violate this foundational principle.

AAOIFI-Aligned Reasoning

The Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) provides frameworks for evaluating novel financial instruments by mapping them onto classical Islamic contract categories. AAOIFI’s approach to cryptocurrencies evaluates each product case-by-case using established Shariah contracts rather than issuing blanket rulings.

For staking mechanisms, AAOIFI-aligned analysis focuses on: whether capital guarantees exist, whether returns are contractually fixed, whether real ownership is maintained, whether productive activity occurs, and whether the contract resembles classical permissible forms.

Is Staking Equivalent to Riba?

Structural Comparison

Critical Distinctions

Riba fundamentally involves guaranteed excess over principal in a lending relationship. Islamic law prohibits this because it creates wealth transfer without risk-sharing or productive contribution. The defining characteristic is the guarantee: lenders receive predetermined returns regardless of borrower’s business outcomes.

Tezos staking diverges from this structure in several dimensions. First, no lending occurs—delegators retain ownership and custody of their XTZ tokens. Second, returns are not guaranteed; they vary based on network inflation rates, validator performance, transaction fee volumes, and baker commission structures. Third, bakers perform actual computational validation work that secures the network.

However, some scholars raise concerns about inflationary reward models. If all token holders stake and receive proportional inflation rewards, the economic effect resembles universal interest distribution where purchasing power remains relatively constant. This argument suggests that inflation-based rewards may function as disguised interest when viewed systemically.

Is Tezos Staking a Form of Lending?

Tezos delegation categorically does not constitute lending (qarḍ) under Islamic jurisprudence. In Islamic law, a loan requires transfer of ownership from lender to borrower, with the borrower assuming responsibility for the asset.

Ownership Analysis

When delegating XTZ, tokens never leave the delegator’s wallet address. Smart contracts on Tezos allow delegation while maintaining custody—a technical feature with significant Shariah implications. Cryptographic signatures prove that delegators retain complete control and can revoke delegation instantly without baker permission.

Contract Classification

Islamic jurisprudence requires identifying the appropriate contract category (aqd):

Qarḍ (Loan): Requires ownership transfer; borrower uses assets and returns equivalent. Tezos delegation does not fit this category because ownership never transfers.

Wakalah (Agency): One party authorizes another to act on their behalf. Delegation partially resembles wakalah, as bakers act on behalf of delegators for validation purposes.

Ju’alah (Service Reward): A unilateral promise to compensate anyone who achieves a specified result. Recent fatawa from Darul Iftaa Chicago and AAOIFI scholars classify staking under this framework. The baker performs validation work, and upon successful completion, receives rewards that are partially shared with delegators.

The ju’alah classification appears most appropriate for Tezos staking because it captures the essential dynamic: delegators contribute capital that enables bakers to perform validation services, and rewards flow from successful task completion rather than from loan repayment.

Arguments That Say It Is Halal

Network Security Participation

Staking represents active participation in blockchain infrastructure maintenance, analogous to providing computational services. Validators perform real work—verifying transactions, maintaining consensus, securing the network against attacks—that has measurable economic value.

Ju’alah Contract Framework

The strongest halal argument positions staking as a ju’alah contract, where validators receive compensation for completing specified validation tasks. AAOIFI defines ju’alah as “a contract in which one party offers specified compensation to anyone who achieves a determined result in a known or unknown period”. Staking rewards fit this definition: the protocol offers compensation for successful block validation.

No Guaranteed Principal Increase

Unlike interest-bearing instruments, staking does not guarantee returns. Rewards fluctuate based on network conditions, validator performance, and participation rates. Delegators face genuine risk of reduced rewards if network participation increases or if their chosen baker performs poorly.

Inflation Distribution Model

Rather than creating new value through interest, staking distributes newly minted tokens to network participants who contribute to security. This resembles equity dilution in corporations where new shares are issued to reward contributors, rather than interest payments on debt.

Musyarakah (Partnership) Analogy

Bank Negara Malaysia and Shariah scholars recognize staking as potentially resembling musyarakah—a partnership where participants contribute capital and share in profits and losses. Delegators contribute capital (staked tokens), bakers contribute labor and infrastructure, and both share the resulting rewards proportionally.

Arguments That Say It Is Haram or Doubtful

Inflationary Dilution Resembling Interest

Critics argue that inflation-based reward systems function economically like interest. When all token holders stake and receive proportional inflation rewards, the net effect may be maintenance of relative purchasing power—similar to interest compensating for currency devaluation. Non-stakers experience value dilution, creating a compulsion to stake that resembles interest-based systems.

Yield Expectation and Passive Income

Although technically variable, staking yields in mature networks become relatively predictable. When rewards stabilize around consistent percentages (5-6% for Tezos), the practical distinction from fixed interest narrows. This predictability may constitute a form of guaranteed return that violates riba prohibitions.

Risk Asymmetry Concerns

While staking involves some risk, the risk profile differs from classical Islamic partnerships. Delegators face primarily price volatility risk (common to all cryptocurrency holdings) rather than operational business risk. The separation between capital providers (delegators) and service providers (bakers) may not constitute genuine risk-sharing in the musyarakah sense.

Absence of Tangible Asset Backing

Cryptocurrencies lack underlying productive assets, raising concerns about whether they constitute valid property (mal) under Islamic law. If the base cryptocurrency is not permissible, staking rewards derived from it would similarly be impermissible.

Speculation and Gharar

The extreme price volatility in cryptocurrency markets introduces excessive uncertainty (gharar). When the primary motivation for staking is speculative price appreciation rather than utilization of the blockchain’s actual services, it may fall into maisir (gambling) territory.

Gharar in Reward Mechanisms

The variable nature of staking rewards, while avoiding riba concerns, introduces gharar. Delegators cannot know with certainty what compensation they will receive, and outcomes depend on factors largely outside their control.

Tezos vs Ethereum Staking: Shariah Comparison

Lockup Requirements

Ethereum 2.0 requires validators to lock 32 ETH with no immediate withdrawal option, creating liquidity constraints that may increase gharar. Tezos allows instant delegation changes without lockup, reducing uncertainty and providing greater flexibility aligned with Islamic principles of fairness.

Slashing Risk

Ethereum implements aggressive slashing penalties for validator misbehavior, potentially resulting in substantial capital loss. Tezos has minimal slashing risk with smaller penalties, reducing the excessive uncertainty (gharar) component.

Centralization Concerns

Ethereum’s high capital requirements (32 ETH, approximately $50,000-100,000 depending on market conditions) create barriers that favor wealthy validators. Tezos’ lower barriers and liquid delegation promote broader participation, aligning better with Islamic principles of economic accessibility.

Yield Structure

Both networks distribute inflationary rewards plus transaction fees. However, Tezos’ inflation rate decreases over time as total supply grows, while Ethereum’s post-merge economics involve token burning that may create deflationary pressure. Neither structure is inherently more or less Shariah-compliant based purely on yield mechanics.

When Tezos Staking Becomes Problematic Islamically

Custodial Platform Lending

Staking through centralized exchanges like Binance or Coinbase frequently involves lending your cryptocurrency to the platform, which then uses it for various purposes including interest-based lending. This arrangement transforms staking into an impermissible loan with guaranteed returns.

Guaranteed Return Promises

Any platform promising fixed APY (annual percentage yield) or guaranteed returns violates Islamic prohibitions against riba. AAOIFI standards explicitly categorize “fixed or guaranteed earn/APY products” as absolutely not Shariah-compliant.

Leverage and Margin

Using borrowed capital or leverage to stake cryptocurrency introduces riba directly. Borrowing at interest to earn staking rewards constitutes layered prohibited transactions.

Interest-Bearing Exchange Platforms

Even without explicit guarantees, staking through platforms that commingle funds and engage in interest-based DeFi lending contaminates the staking activity. Recent AAOIFI analysis warns that custody remaining with exchanges creates “qabd risk” where Shariah compliance cannot be verified.

Haram Underlying Activities

If the Tezos network itself or specific dApps built on it facilitate prohibited activities (gambling, interest-based lending, adult content), staking that secures such activities becomes impermissible. Validators must assess whether their validation work supports halal purposes.

Staking vs Lending: Critical Distinctions

Is Staking the Same as Crypto Lending?

No. Staking and crypto lending represent fundamentally different mechanisms with distinct Shariah implications.

Crypto lending involves transferring ownership of cryptocurrency to a borrowing platform, which uses the funds for interest-generating activities and pays depositors fixed returns. This structure clearly constitutes riba—guaranteed excess compensation in a lending relationship.

Staking (when done non-custodially) maintains delegator ownership while enabling validators to perform network security functions. Rewards come from protocol inflation and transaction fees, not from lending activities.

Structural Contract Differences

Why Lending Is Typically Riba-Based

Crypto lending platforms like BlockFi, Celsius, and centralized exchange lending programs operate by paying depositors fixed or predictable returns funded by charging higher interest to borrowers. This intermediation model mirrors conventional banking’s interest mechanism—exactly what Islamic finance prohibits.

The guaranteed or semi-guaranteed nature of returns, combined with the loan structure, categorizes these platforms as riba-based regardless of terminology. Islamic law prohibits both giving and receiving riba.

Bitcoin Mining vs Tezos Staking: Islamic Comparison

Mining as Service Provision

Bitcoin mining involves expending computational resources and electricity to solve cryptographic puzzles, with successful miners receiving newly minted bitcoin plus transaction fees. This resembles ju’alah—compensation for completing a specified computational task.

Resource Input Differences

Mining requires substantial upfront capital investment (mining equipment, facilities, electricity contracts) and ongoing operational costs. Staking requires capital lockup but minimal operational expenses. From a Shariah perspective, both involve real resource contribution, though the nature differs.

Block Reward Model Similarities

Both mining and staking distribute newly created cryptocurrency as compensation for network security services. The inflationary mechanism is structurally similar, with protocol rules determining reward amounts.

Environmental Considerations

Bitcoin’s energy-intensive Proof-of-Work raises ethical questions about resource waste that some Islamic scholars consider relevant to permissibility assessments. Tezos’ energy-efficient Proof-of-Stake avoids this concern, potentially aligning better with maqasid al-shariah (objectives of Islamic law) regarding environmental stewardship.

Relative Shariah Assessment

Neither mechanism is inherently more permissible than the other from a pure contract perspective—both can be structured as ju’alah (service compensation). The key distinction lies in resource expenditure: mining involves labor and capital consumption, while staking primarily involves capital opportunity cost.

Practical Decision Framework for Muslims

Assessment Criteria

Understand Technical Risk: Before staking, comprehend how the Tezos protocol works, what validators do, the nature of rewards, and potential risks including price volatility and validator underperformance.

Maintain Custody: Use non-custodial wallets (Temple Wallet, Kukai) where you control private keys and delegate directly to bakers without transferring ownership. Avoid centralized exchange staking programs.

Avoid Leverage: Never borrow capital to stake, as this introduces clear riba into the transaction structure.

Reject Guaranteed Yields: Stay away from platforms promising fixed returns, as these guarantees constitute riba. Legitimate staking rewards must be variable and dependent on network performance.

Treat as Network Participation: Conceptually frame staking as contributing to blockchain infrastructure rather than passive income generation. This mindset aligns with the ju’alah service compensation framework.

Decision Matrix

If you:

- Use non-custodial wallets with self-custody

- Delegate to transparent bakers with disclosed fee structures

- Accept variable returns without guarantees

- Verify that Tezos network activities are predominantly halal

- Understand and accept the technical and price risks

Then: Staking may fall under the permissible ju’alah framework according to recent Shariah analyses.

If you:

- Stake through centralized exchanges

- Receive guaranteed APY promises

- Use leverage or borrowed capital

- Lack understanding of the mechanism

- Stake purely for speculative price gains

Then: The activity likely contains prohibited elements (riba, gharar, maisir) and should be avoided.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Tezos Halal?

Tezos as a blockchain platform is generally considered permissible by Shariah screening services, as its core technology does not inherently involve riba, and its governance and smart contract capabilities can support halal applications. However, individual activities conducted on Tezos must be evaluated separately.

Is Staking Halal in Islam?

Staking permissibility depends on structural details rather than the label “staking” itself. Non-custodial staking without guaranteed returns, structured as service compensation (ju’alah), has support from contemporary Shariah scholars. Custodial staking with guaranteed yields is considered haram.

Is ETH Staking Shariah Compliant?

Ethereum staking faces similar analysis to Tezos, with additional concerns about lockup periods increasing gharar. Some Shariah-compliant staking services have emerged for Ethereum, focusing on non-custodial approaches. The January 2026 launch of Shariah-compliant ETH staking platforms indicates growing scholarly acceptance under specific conditions.

Is Stake Investing Halal?

The term “stake investing” is ambiguous. If referring to equity investment (buying stakes in companies), permissibility depends on whether the company’s business model and capital structure comply with Islamic screening criteria. If referring to cryptocurrency staking, see the detailed analysis above.

Is TRX Staking Halal?

TRON (TRX) staking would require separate analysis of TRON’s network purpose, the nature of its staking mechanism, and whether activities on the TRON blockchain predominantly serve halal purposes. The same principles apply: avoid custodial platforms, guaranteed returns, and leverage.

Balanced Conclusion

Scholarly opinions diverge on Tezos staking permissibility because the practice sits at the intersection of novel technology and centuries-old jurisprudential principles. The lack of consensus reflects genuine interpretive challenges in applying concepts like riba, gharar, and ju’alah to decentralized network validation.

Context matters profoundly. Staking through non-custodial means, with transparent variable rewards and genuine participation in network security, presents the strongest case for permissibility under the ju’alah framework. Conversely, custodial staking with guaranteed returns clearly violates riba prohibitions.

Contract structure determines Shariah status more than superficial labels. The critical questions are: Does ownership transfer occur? Are returns guaranteed? Is productive activity involved? Does the arrangement resemble classical prohibited contracts?

Blind participation without understanding the technical, economic, and contractual dimensions is dangerous both financially and religiously. Muslims considering Tezos staking must educate themselves on the protocol mechanics, assess their personal risk tolerance, and preferably consult qualified Shariah scholars familiar with blockchain technology.

Informed participation based on understanding the ju’alah service compensation framework may change the ruling for individual situations. However, uncertainty remains, and those seeking absolute certainty may prefer to avoid cryptocurrency staking altogether until broader scholarly consensus emerges.

The rapid evolution of both blockchain technology and Islamic finance scholarship means that today’s analysis may be refined as both fields develop. Muslims engaged in this space should remain connected to ongoing scholarly discussions and be prepared to adjust their practices as understanding deepens.